News of traumatic global events, such as war, natural disasters, and gun violence, is never far from our screens or minds today. Watching these events, we might experience feelings of fear, anxiety, sadness, anger, and so many other complex emotions. To counter these feelings and practice self-empathy during a crisis, we can pause and ask ourselves: “What else is true?”

In these challenging moments, it’s especially important to remind ourselves of the nourishing people and things in the world around us. Whether it’s a cherished memory with a loved one, or the knowledge that there are so many helpers in every community, we should remember that even in the face of adversity, there is still beauty, kindness, and love in the world. When we find strength in our surroundings, we build our own emotional resilience and increase our capacity for empathy for others.

Empathy is an important skill that helps us understand and care about others’ feelings and experiences. Empathy has three components: feeling, thinking, and acting. We recognize someone’s feelings and feel their emotions with them (emotional empathy), think about their unique situation and perspective (cognitive empathy), and feel moved by our feelings and understanding of their situation to want to help them (behavioral empathy). We can practice empathy towards ourselves, people in our community, and even people living in faraway places who may initially seem different or unfamiliar to us. Empathy enables us to see the shared humanity in all of us, and empowers us to make a positive impact on the world.

During challenging times, it’s important that we are also empathetic towards ourselves. To be compassionate towards others, we must first ensure that we are in our “resilient zone”.

In this article, we will explore healing-centered and trauma-informed strategies for practicing self-empathy during a crisis. We’ll learn to recognize signs of stress in ourselves and children, and gain ideas for how we can nurture our resilient zone. These strategies will also help increase our capacity to empathize with others, and become a source of support and comfort for them.

The “Resilient Zone” Explained: A Key to Practicing Self-Empathy During a Crisis

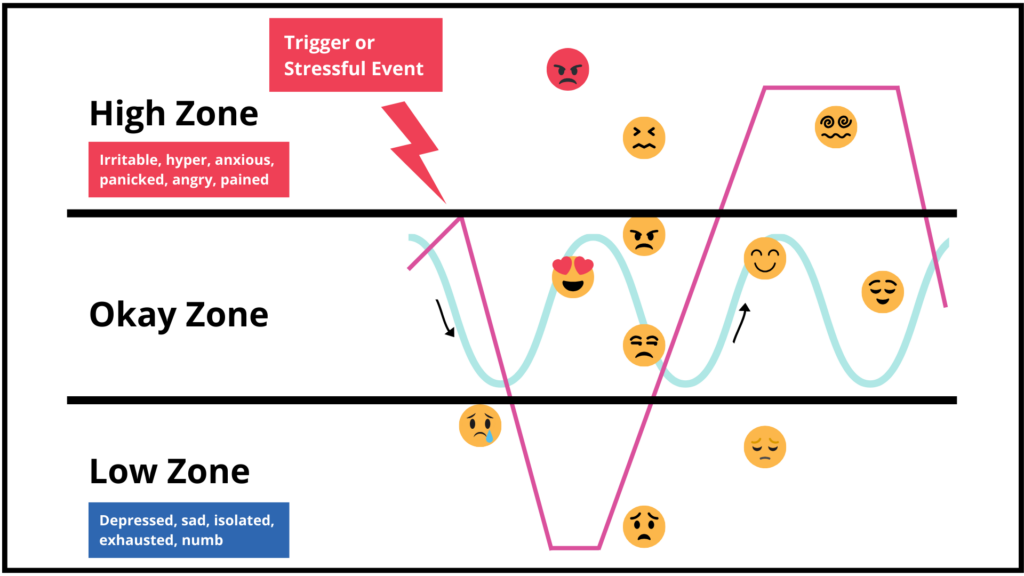

We all experience different zones throughout the day, which can affect our feelings. Our mind and body also work differently depending on which zone we are in.

The resilient zone, also known as the “okay zone”, represents our emotional equilibrium and ability to handle stress. When we’re within this zone, we are able to handle challenges more effectively, make positive and healthy choices, and maintain a balanced emotional state. Nurturing our resilient zone is important in the context of practicing self-empathy during a crisis. A stronger resilient zone enables us to support our own well-being, and also extend our empathy to those who are in need.

When we encounter stressors, such as watching the news from a war zone, we might leave our okay zone, and enter a “high zone” or “low zone”. In a high zone, we might feel anxious, panicked, or angry. In a low zone, we might feel depressed, isolated, or exhausted. You can learn more by watching this video.

Take a moment to reflect:

- What types of feelings and sensations do you associate with an okay zone? What about a high or low zone?

- Which experiences move you out of your okay zone, and into a high or low zone?

- Do you think these zones look different for adults and children?

What Are Signs That We Are Experiencing Stress, and Might Be in a “High Zone” or “Low Zone”?

When adults experience a traumatic event, they may enter a high or low zone, and exhibit emotional, physical, or behavioral reactions. For example, they might feel angry, afraid, depressed, tired, numb, hopeless, or anxious. There may be physical reactions, like a rapid heart rate and breathing, tight muscles, trembling, or stomachaches. They might have trouble sleeping, feeling present, remembering details, or making decisions. They might seek solitude, be prone to negative thinking, have angry outbursts, or become overly dependent on others.

Have you experienced any of these reactions due to stress? Which zone do you associate these reactions with?

Children can have a variety of responses to stress, and their reactions may also be emotional, physical, or behavioral. Children’s responses will manifest differently depending on their developmental age, temperament, and safety of the environment.

When they are under the age of five years old, toddlers may demonstrate regressive behaviors. Young children may have more frequent temper tantrums and angry outbursts. They may have increased hitting, biting, kicking, and throwing things. They may cry more frequently or experience an increase in clinging behavior.

As children become older, primary and secondary school-aged children might manifest different reactions. They may experience many emotional reactions, including fear, anxiety, depression, nightmares, night terrors, and numbness. Their thoughts may be occupied by fears of separation from their primary caregivers and worry about their own death or the death of family members.

Children of all ages may also experience a variety of physical responses, including somatic reactions like headaches and stomachaches. They may report a rapid heartbeat and fast, shallow breathing. Some experience nausea and vomiting. Dissociation can be experienced as inattention, resulting in memory problems and not being in touch with the present moment. Some physical responses can include hyperactivity and an overactive startle response. Sleep problems may begin with either insomnia or sleeping too much.

Behavioral responses can be dramatic for some children with abrupt changes. Some children lose interest in activities they used to enjoy. There can be an increase in aggression and looking for possible threats. Some children isolate themselves and have difficulty making friends. There may also be academic challenges along with difficulty in paying attention.

What Are Some Strategies That Help Build and Expand Our “Resilient Zone”?

Practicing self-empathy during a crisis starts with learning resiliency skills, cultivating our well-being, and ensuring we do not get stuck in a high or low zone. As educators and caregivers, it’s important to stay within your own resilient zone so you are able to take care of yourself and better support the children in your life.

For example, you might:

- Identify a supportive family member or friend whom you can speak to, and share your emotions, thoughts, and concerns with each other

- Take time for mindfulness and self-care in a way that is meaningful to you (e.g., by taking walks in nature, spending time with loved ones, or practicing deep breathing exercises)

- Check-in with your emotional and mental state before reading or watching the news, and limit your exposure if you are feeling stressed or anxious

- Seek out uplifting content that focuses on inspiring stories and acts of kindness

- Develop a sense of purpose by supporting causes that you care about (e.g., through volunteering, raising awareness, or donating money)

- Learn and practice the Reset Now! strategies

- Download the free iChill app that includes six skills, including the Help Now to Reset Now! skills

- Remember, “What else is true?”

What are some ways children can practice self-empathy?

Since children are still developing their self-empathy skills, they may need support from a trusted adult. Use the following strategies to help children identify and express their emotions, find calming resources, and become more resilient.

When children are under three years old, infants and toddlers often do not understand the meaning of what is going on, but will react to the emotions and behaviors of those around them. They need reassurance through physical contact and simple, comforting communication.

For example, you might:

- Help them “ground” by holding and rocking them

- Reduce stimulation to calm a distressed infant

- Express words of comfort like: “I am here.”

- Provide them with resources like a stuffed animal, blanket, or book

As they enter lower primary school ages (3-6 years old), children’s understanding of these events is limited. It’s helpful to share short, simple explanations, paired with physical closeness and reassurance of their safety. They also benefit from engaging in normal activities.

For example, you might:

- Say statements like: “We are safe right now. I am with you.”

- Provide space for them to express their emotions through playing and drawing

- Facilitate mindfulness exercises, such as Grounding Like a Tree and Mindful Walking

- Encourage them to draw a picture of something that makes them feel happy, like their favorite toy, friend, place, or animal

For older primary-school aged children (ages 6-10 years old), they may partially understand what is going on, but will often create their own interpretation of events. They need facts and clarification, and want to feel safe.

For example, you might:

- Provide space for them to share their emotions with you, and validate their feelings as being normal and understandable

- Listen to their questions and try to answer them (or search for answers together)

- Encourage them to participate in normal activities such as games and schoolwork

- Limit their exposure to TV, social media, and other “adult talk” due to their partial understanding of these events, and because they are looking and watching for your reaction

- Help them identify and remember Personal Resources that foster feelings of strength, peace, and joy

- Lead mindfulness exercises such as a Body Scan Meditation or sending Three Kind Wishes into the world

- Ask open-ended questions to explore their thoughts and feelings about world events (e.g., “How do you feel about what’s happening? What have you heard about it?”)

As children become adolescent-aged (11-18 years old), they might try to keep their feelings inside. They understand what is going on, and have their own thoughts and perspectives. Try to be available and watchful, but understand that they might prefer to talk to their peers.

For example, you might:

- Create space for them to share their emotions with you (and consider sharing your own feelings to start the conversation), and validate all emotions as being normal and understandable

- Stay involved and direct their energy in productive ways that build their sense of well-being and maintain safety

- Encourage them to help others with tasks, such as sharing self-care skills with younger children or engaging them in play

- Share options for self-help activities, such as Gratitude Journaling and the Reset Now! strategies

- Guide them to create and post positive messages on social media (e.g., sharing hope and wellness skills)

- Discuss how some images on social media (e.g., graphic photos from a war zone) can cause us to experience intense emotions, and prompt them to restore a sense of balance by sharing some favorite images with each other (e.g., something that makes you smile, like a cute puppy or cat)

- Engage them in exploring peaceful solutions to problems and invite them to think about ways to foster peace in their local communities

Most importantly, understand that the knowledge of war and its implications can cause an existential crisis in some teenagers. If you were already concerned about their mental health before traumatic world events, check in with them to assess whether they are at risk of self-harm. If needed, seek out a mental health professional for additional support.

By nurturing our resilient zone and practicing self-empathy during a crisis, we not only strengthen ourselves but also become better equipped to offer support and compassion to people facing their own hardships during times of crisis.

To continue exploring more self-empathy resources for children, join us at Empatico.